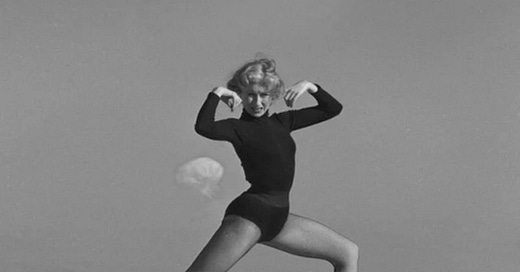

I’ve spent the last hour looking at and reading about photos of a woman doing interpretive dance while an atomic bomb explodes in the background.

They were some of the first things I saw this morning and, still bleary eyed from sleep, I thought they were fakes, composites; but no, it turns out that on April 7th 1953 (almost 70 years ago to the day), Sally McCloskey, a ballerina, danced atop Angel’s Peak, Nevada, while some 40miles behind her humanity reckoned with itself, testing its tools, flexing its muscles.

As far as images go they’re pretty amazing, if not unfortunately low-resolution. But they’re kind of hard to get your head around. Obviously you can make sense of the simplicities of it, a woman dances, a bomb explodes, the desert an ocean of grey; but beneath it all hums the hellish tone of destruction, our entire history of warfare, from the first collisions in the primordial soup, to territorial disputes and wars of attrition, to developing weapons that can bring about mutually assured destruction.

And still we dance.

It’s like something out of so many things—this dichotomy is a rich well drawn from by so many—but for reasons of recent encounter and anniversary it mostly brings to mind Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, which I re-read last week for the first time since I was 17, and Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, which I read for the first time a year ago this Easter weekend.

I guess too there’s a poignancy to seeing these images on the day of the resurrection. I wonder, when the people who first wrote about the crucifixion reckoned with forgiveness and humanity’s awe-inspiring capacity for destruction, if they considered something quite so devastating as what we now possess in our arsenals? And of all those who stand on the side of complete redemption and believe that the sacrifice commemorated by this weekend atones all of all—how does that feel? And without heaven, as many who wrote the greatest tracts on the problem of evil prior to the messiah did not believe in, what is there to be said of salvation, of redemption and atonement, for a species that holds in its hands the ability to wipe itself out?

This is not the place to expound upon such problems in the amount of detail they deserve, and I don’t think that a few pithy remarks can challenge or take down thousands of years of theology. But the older I get the more the problem of evil takes up my thoughts, in ever changing formations. Often taken out of God’s hands and placed into our own. How do we reckon with our capacities?

“It makes no difference,” says Judge Holden in Blood Meridian, “what men think of war. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner.”

So too does the book end with the Judge “dancing, dancing. He says that he will never die.” He is, in many ways, McCarthy’s image of war made flesh. Big and vile and terrifying in his ability to attract men. Note too what lies in vile—the Judge is pure evil.

And still we dance.

In Cat’s Cradle, which in part tells the stories of the children of Francis Hoenniker, one of the (fictional) men at the head of the Manhattan Project, one of them recounts:

“…do you know the story about Father on the day they first tested a bomb out at Alamogordo? After the thing went off, after it was a sure thing that America could wipe out a city with just one bomb, a scientist turned to Father and said, ‘Science has now known sin.’ And do you know what Father said? He said, “What is sin?’

That line, I suppose, as Judge Holden is McCarthy’s image of war, is Vonnegut’s version of Oppenheimer’s quoting the Bhagavad Gita following the first succesful detonation of a nuclear bomb, Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds.

Oppenheimer’s brother would correct people and tell them that no, in fact, the first thing he said following the explosion was just that it works. Whereas Kenneth Bainbridge, another member of the Manhattan project, had this to say in response: Now we are all sons of bitches.

As it stands, I don’t think Christopher Nolan is up to the job, morally speaking, of handling the story of Oppenheimer and the bomb. I’ll still watch it though, out of sheer intrigue, out of perhaps some perverse comfort born of fear and sadness and disgust at the story itself represented on screen.

It is in its own way its own dance.

In one of the photos of Sally McCloskey dancing as the bomb explodes she has a pained expression on her face. An unintentional grimace caught between movements? Or an understanding of it all she couldn’t hide?

It’s sunny here in Glasgow, among the warmest days we’ve had all year, and there is only one thing for it, I’m going to spend my day at the park. I won’t dance. But dancing isn’t just dancing. It’s release and relief in distraction.

“As stupid and vicious as men are,” Vonnegut writes in Cat’s Cradle, “this is a lovely day.”

I think this is my favourite thing you've written. And yes - Nolan, amongst plenty of merits, makes fundamentally conservative films.